Today, I want to look at the relationships between the process of developing more human technologies and the business models that frame those technical developments. Let’s first briefly review the way technologies come to play a role in society, the role of design, and why I believe that business models are an essential part of making more human technologies.

Technologies, their use and meaning in society

The first point is to understand which role technology plays in our society. I have spoken about that at some length in my previous posts so I will only sum up the most relevant points.

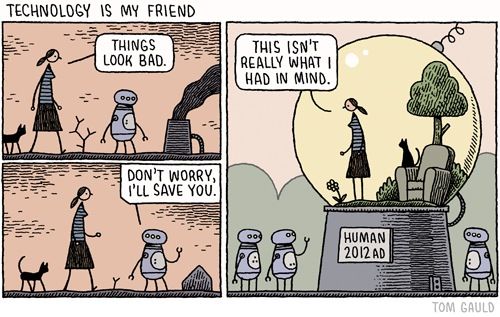

- © Niemann, 2014

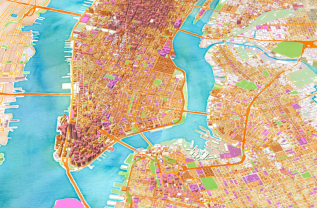

First, technologies, through the way they are being designed, tend to allow, constrain, and draw certain relations in their environment. When light bulbs are designed to only last 100 hours, we can say that the value of obsolescence is embedded in the object. When Apple improves its computer’s interface to be friendly for everyday users (but difficult to tweak for advanced users), it embeds the value of (a certain type of) user-friendliness. When Israel designs its urban and road planning to constrict and isolate Palestinian villages, it puts a certain politic in these objects. When Fairphone redesigns smartphones for longevity and ease of repairability, it embeds its understanding of sustainability in the phone. The list can go on but the point is that technologies are developed with a certain vision of how we should interact with our environment. That is why, we may say that they are ‘political.’

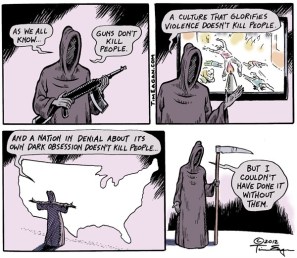

Second, it is not because a technology has values embedded in it that its meaning and use cannot be hijacked. A famous horrific example would be the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Planes, which had been designed for transport, to increase efficiency, and which represent a typical vision of the Western world and globalisation, have witnessed their use and meaning entirely re-appropriated. They became engines of death and, in a sense, the ‘spokespersons’ of the conflict with the Western world, globalisation and its values.

Second, it is not because a technology has values embedded in it that its meaning and use cannot be hijacked. A famous horrific example would be the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Planes, which had been designed for transport, to increase efficiency, and which represent a typical vision of the Western world and globalisation, have witnessed their use and meaning entirely re-appropriated. They became engines of death and, in a sense, the ‘spokespersons’ of the conflict with the Western world, globalisation and its values.

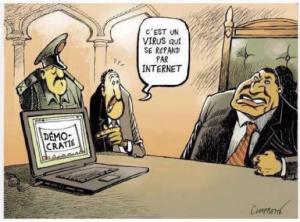

This leads me to the last point: technologies are inescapably tied and developed within socio-technical systems. They become political and situated in space as the result of iterative process of interaction with the socio-technical components of their environment. They gain relevance when they are compatible with existing infrastructures, value judgements, economical settings, etc. This complex and ambivalent position, which extend well beyond the technology itself, is what we need to deal with when we attempt to make more human technologies.

The role of business model in the making of human tech.

The key problem is that even though this complex position is broadly acknowledged, most of the focus on responsible innovation is on the scientific and technical process. I think that we should take a deeper look at the relationships between the development of technologies and the business structures, values, and models from and with which they emerge.

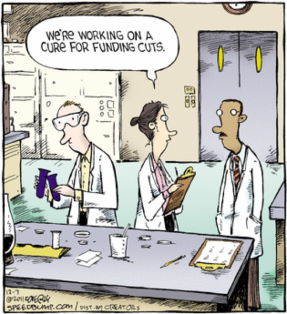

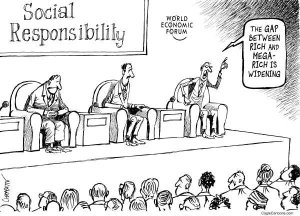

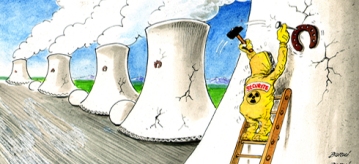

- ©Dave Coverly, Speed Bump, 2011

It may seem obvious but more often than not scientists and engineers do not really control the visions and expectation that are set as the goals of their research agendas. Let’ take the example of the development of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs). Originally, the biologists working on GMOs were enthusiastic about the possibility of greatly diminishing the use of pesticides which had been heavily criticised in the 1960s. Fast forward a couple of decades later: as a result of the institutional structure they evolved in and the business model of biotech industry, it turned out that the profitable option was the opposite of their hope – that is developing organisms that could withstand the use of pesticide. The point I want to emphasise is that it is not enough to look at the drive of the engineers developing a technology. The business models (as well as many other infrastructural aspects) are at least as essential in the development of more human tech.

Making Human Tech. Through Re-designing of the Business Model

So perhaps we can use the same perspective discussed (in the previous posts) about making more human tech. (i.e. by thinking with anticipation, inclusion and reflexivity about our desired futures in order to (re)design our technologies) to also develop more human businesses?

Recently, I discovered a company called RiverSimple. It is an innovative British business that aims at designing a new business model for sustainable mobility. In one of the interviews, RiverSimple’s CEO Hugo Spowers made a compelling case why the car industry fails to work towards sustainability. As he stated: when you are in the business of selling cars to your customer you make your profit by selling cars that are as expensive as possible, as unreliable as possible, and have a short life, etc. The approach of RiverSimple is to redesign their business model to align the profit making with broader social goals. By doing something as simple as leasing cars instead of selling, RiverSimple maintains the ownership of its vehicles. As a result, the mechanism of profit making includes aspect such as: having a vehicle that last as long as possible, consumes as little as possible, demand as little maintenance as possible, etc. Governing our futures can also be done by making cars, but it is not only the design of the car that has to change. The business model (among other things) will also need to bifurcate.

Making Human Technologies = aligning social goals, technical design & business model?

My title may be a bit misleading. I believe that making human tech is not about focusing on businesses or technologies themselves but about changing the way we think about the relationship between the development of technologies, of business models, of policies, etc. The point is that we cannot just focus on the development of the technology, instead we need an integrative approach where developing and researching a new technology comes in hand with different business models. In such way we also can make sure that producing the making of human tech a profitable – and scalable – endeavour.

And you what do you think? Does that seem like a good idea? Let’s discuss it in the comment section!

If can we agree that values-less design is simply impossible (see my older posts). And that by making the technologies we will be living with, we are contributing to make a technological culture which impacts society, businesses as well as you and me. Then, the question is what can we do in practice to make technological innovation more human? In this blog post, I want to review the so-called approach of ‘Value Sensitive Design,’ a methodology which aims at finding a way to both identify the values that should matter and to embed them in the technologies. Now, let’s take a look at how we can get technology to work with us.

If can we agree that values-less design is simply impossible (see my older posts). And that by making the technologies we will be living with, we are contributing to make a technological culture which impacts society, businesses as well as you and me. Then, the question is what can we do in practice to make technological innovation more human? In this blog post, I want to review the so-called approach of ‘Value Sensitive Design,’ a methodology which aims at finding a way to both identify the values that should matter and to embed them in the technologies. Now, let’s take a look at how we can get technology to work with us.

Today, I was reading

Today, I was reading  What is the relation between technologies and values? The answer we often hear is that mixing technologies with values

What is the relation between technologies and values? The answer we often hear is that mixing technologies with values

Another reason, a more economical one, relates to the perceived role of innovation in our modern economies. Innovation as an economical necessity is an idea that emerged in the late 1960s under the concept the ‘knowledge society’.

Another reason, a more economical one, relates to the perceived role of innovation in our modern economies. Innovation as an economical necessity is an idea that emerged in the late 1960s under the concept the ‘knowledge society’.